Design and Behavior, Part 2

When you tell a social media platform how you feel, it will use this information to manipulate you (just like your toxic ex)

Last week I wrote about how structural factors of social media platforms directly modify the likelihood of arguing. I looked at population size, age of existence, and demographics of use (including political skew) - and these all contributed to some extent. But they didn’t fully explain everything. I also cited Davenport et al. (2014), which found that narcissism was associated with more Twitter use for Millennials, but more Facebook use for Gen X and Baby Boomers. This showed that problematic usage of social media wasn’t necessarily dependent on either platform type or generational factors, but it did show that narcissists use these platforms differently, indicating that the design and purpose of the various platforms influenced how people are likely to behave in order to get the most reward.

From that, we might have concluded that Facebook - wherein the number of friends was associated with narcissism - would be a more peaceful place compared to Twitter, wherein the more dramatic, spicy posting is encouraged by the design. But another study by Baughan found the opposite: Facebook is one of the worst platforms for arguing by far.

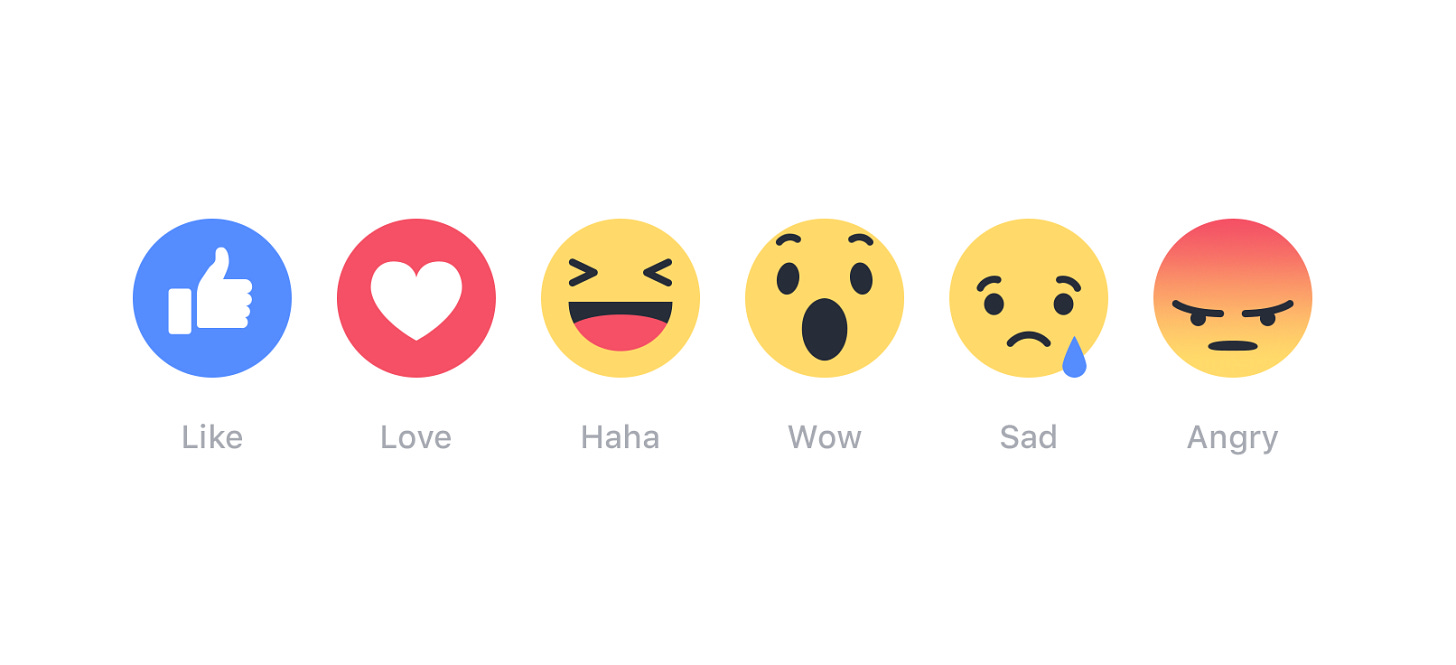

I concluded with my own hypothesis, which I have been thinking about for quite some time. I think the largest contributor to why Facebook is so fighting-friendly is because of the diversity of the reaction options.

Take a second to reflect on your own experience, if you are or have ever been a Facebook user after February 24th, 2016 (the date when these things premiered, extending the options for the first time beyond the humble thumbs up). Have you ever been casually scrolling and almost blew right past a post but stopped because you saw that it had a shit load of “wow”s and “angry”s and “sad”s? Of course you have. Of course you have.

Again I want to say that arguing occurs on all social media platforms. I’ve seen it on every last one of ‘em. Instagram, Reddit, obviously Twitter. But in my anecdotal experience, and in line with the studies I have cited above, fighting happens on Facebook more than any other platform. And I would ask you to stop and reflect, especially if you are old enough to remember Facebook use in 2012: was it as contentious as it was in 2016 and later? My own experience tells me “absolutely not,” that it got meaningfully more contentious and addicting in 2016 and later. I remember having political disagreements with people in 2012 on Facebook, and it wasn’t remotely as contentious as it became four years later. I remember blocking people less back then, too.

Now, obviously, there’s a big orange elephant in the room. Yes, Donald Trump won the Republican primary a few months after the Facebook reactions launched, and just about everyone across the spectrum agrees that he brought in an era of coarsened language and increased hostility. His devoted followers often cite his propensity to “tell it like it is” as the biggest selling point. But it goes beyond just what he says: it’s the medium wherein he says it. Debra Lee, a chief executive at BET and (at least in 2016) a Twitter board member, stated emphatically that the “celebrity style” way in which Trump used Twitter helped him win the 2016 election.

“He was able to use Twitter and to use social media to get around conventional media and not deal with having to buy time on media or deal with newspapers or whoever he didn’t like.”

There’s data to back it up, too. David Robinson, a statistical analyst, concluded that his Twitter usage made Trump more likely to garner “interest.”

So why am I still insisting that Facebook is the problem when all I have mentioned so far is Twitter? It’s because even if you didn’t have Twitter, you saw his tweets. Probably on Facebook.

If you examine just sheer size of user base alone (In 2017, Twitter was estimated to have 317 million active monthly users and Facebook 1.87 billion), there is a statistical probability that you encountered Trump’s tweets on Facebook (or an article about them). And you reacted to them. Probably with an anger or a laugh react. And then you probably shared it, where other people reacted. And commented. And you replied. And they replied. And you replied again. And the next thing you know, you had lost a whole ass afternoon.

This is the structure and purpose of Facebook in the modern internet. We know their algorithms intentionally drive “engaging” content to the top of your feed. But whether or not something is engaging is not driven by how much you like it, it’s driven by how likely you are to slap a react on it and leave a bunch of comments. Preferably over the course of several hours, forcing you to keep coming back to the app so you have to scroll past advertisements and keep arguing with your uncle or the stranger you’ve never met and never will talk to again. This is why Russians seeking to sow discord in the 2016 election turned most often to Facebook over all other platforms (and they did it by simply pitting people with opposing views against each other; their main tactic wasn’t even disinformation).

Twitter has likes and retweets, Reddit has upvotes and downvotes, and other platforms have other tools with which to measure engagement (and they all do, and their internal mechanisms respond to that). But Facebook is the only one with a diversity of reactions, and even better, it is a one-for-one representation of emotion, and emotion is the driver of content. Especially when paired with morality.

Brady et al. (2017) found that including morally-oriented, emotionally charged language can boost the diffusion of a tweet by a factor of 20% per word.

Across three contentious political topics, moral-emotional language produced substantial moral contagion effects (mean IRR = 1.20, or a 20% increase in retweet rate per moral-emotional word added), even after adjusting for the effects of distinctly moral and distinctly emotional language, as well as other covariates known to affect retweet rate.

In other words, it wasn’t just a tweet structured to talk about right and wrong, and it wasn’t just tweets with strong emotions. It was tweets with emotionally-charged moral arguments that did the best.

There were interesting differences, too. Moral-emotional language, whether oriented towards the positive or negative, had different effects on the “virality” of each given post depending on the topic. Climate change posts with negatively charges moral-emotional language did tremendously well, whereas the positive ones did poorly. In other words, people angry about climate change consequences retweeted more often, and positive messages were largely ignored. With gun control, both positive and negative orientations boosted “virality.” And with gay marriage, positive messages did the best, and negative ones did poorly. Overall, however, anger and disgust tended to do the best.

But again: these are just tweets. You either like it or leave it alone, retweet it or you don’t. With Facebook, you can do all Twitter can, but you can also visualize your emotional response for all the world to see, for both the post and for each individual comment. You don’t even have to say anything. Imagine the effect size when you can use moral-emotional language, AND your post gets plastered in the visual representation of moral-emotional responses.

Behold, the all-powerful combo: 😡 and 😮.

Ever have a conversation about the way someone reacted to a Facebook post? “Yeah, man, she sad reacted it!” or “She just angry reacted and stopped commenting.” Of course you have. The reaction itself is worth reacting to. I have even been known to say “I wish there was a react for reacts.”

There’s another important point that Brady et al. make that I want you to take away from this. The more emotionally charged the tweet, the better it will do…but only among like-minded people.

Another key finding was that the expression of moral emotion aids diffusion within political in-group networks more than out group networks. With respect to politics, this result highlights one process that may partly explain increasing polarization between liberals and conservatives. To the extent that the spread of online messages infused with moral-emotional contents is circumscribed by group boundaries, communications about morality are more likely to resemble echo chambers and may exacerbate ideological polarization.

Again, this is data is from Twitter, but regarding Facebook, we should expect some similarities in polarization and echo chambers, especially since Facebook has the option to make groups, with rules you must agree to that are enforced by moderators. In my own experience, I often saw overt political messaging in the rules of groups. I often saw situations where even just being perceived as evincing some “wrong” position led to an immediate ban from the group. When I used to moderate groups myself, it was often demanded of me that I ban people for saying the “wrong” things, and from my own anecdotal experience, I saw the bar for what counted as such lower every year. It got to where just disagreeing with someone was seen as equivalent to actively spreading hate. In other words, you aren’t just wrong, you’re evil, and there would be a whole legion of like-minded people agreeing. All with the same slate of emojis. Likes and hearts for those that agree, angers and wows for those that didn’t.

Wouldn’t groups foster more echo chambers? They do, and I’ve seen it happen. But they also foster more fighting, because not every group is overtly political (at least in how they start). I’ve seen groups dedicated to a specific movie or video game rapidly become a place for proxy political battles. I wish I could give you more than my anecdotal experience (I moderated multiple groups for almost a decade, some overtly political and some oriented to avoid politics, though they always failed to stay so), but there are not many systemic reviews of these phenomena. It’s definitely an area that more researchers should spend some time on, because as Brady et al. say,

“Twitter and other social media platforms are believed to have altered the course of numerous historical events, from the Arab Spring to the US presidential election. Online social networks have become a ubiquitous medium for discussing moral and political ideas.”

I’ll keep writing about the topic, though. Interesting studies are being done, and governments around the world are taking action on social media in different ways (Florida just passed the strictest social media regulations in the country, for example).

Let me know what you think of the topic. I want to hear about your thoughts and experiences!

In the meantime, though, consider getting off social media. At least Facebook, anyway.