After spending years wondering why people are inherently drawn to taking pictures of themselves, French photographer Augustin Lignier designed an art piece inspired by the work of radical behaviorist B.F. Skinner, who is famous (or infamous, depending on your perspective) for designing the glass boxes where rat behavior could be studied.

The crux of the “operant conditioning chamber” — or “Skinner box” as they became known — is simple: the rat pulls a lever and gets a reward or punishment, with some kind of treat or drug as the former and something painful (usually an electric shock) as the latter. It’s actually a really important innovation in psychological research with highly replicable results that generalize to other species including our own.

Lignier’s piece revolves around his own “Skinner box,” wherein two rats (named after himself and his brother) were placed in a two-story chamber where they could climb up into the second level to push a lever and receive a sugary treat. Meanwhile a camera would snap their picture.

Personally I couldn’t help but imagine what it must have been like for the rats, periodically going upstairs in their weird new apartment to push the cookie button and for a fraction of a second be blinded by a mysterious divine light.

The piece is a commentary about selfies and social media, of course, and shouldn’t be confused with actual research. For one, it’s a sample size of two, and for another, it doesn’t take rigorous psychological training to infer that the rats were motivated by the sugar, not the selfie. The artist himself agreed: “Honestly I don’t think they understood it,” said Mr. Lignier. Again, importantly, this is an art piece, not an actual scientific study.

There is still a core truth to the project that has been supported by actual research, though. (I know, I know, “what if phones but too much.” Not the point I’m making so bear with me.) When something new (the lever) gets attached to what is called an “unconditioned stimulus” (the treat), you start to associate the former with the pleasure of the latter. When the conditioning is designed the right way, you’ll even experience quite a bit of pain in order to reach that pleasure.

For well over a decade now people have been writing about how social media exploits our dopaminergic system to keep us hooked. “Slot machines” are the most common comparison (and quite justifiably so): in psychological research terminology, both social media and gambling use the conditioning system called a “variable schedule of reinforcement.” This means that you don’t always gets the treat when you push the lever. People will pull the slot machine’s handle again and again and again with nothing happening just on the offchance that something good will.

Lignier also put his “selfie rats” on a variable reward schedule, and in line with what science has already found, the rats kept pushing the button like crazy, sometimes even ignoring the sugar. That’s right: with the right reward schedule, the reward itself becomes less meaningful than the conditioned behavior. This helps explain why people develop gambling addictions and substance use disorders, for example.

Variable reward schedules are the strongest form of reinforcement. Consider: every pull of the slot machine costs money, and social media often “punishes” you with negative stimuli. It’s not reward versus nothing, it’s that you become so fixed on getting the reward you don’t mind receiving pain.

Or rather, you learn to ignore the pain. Social media works no differently: a recent study found that over 50% of Gen Z suffers from anxiety, and over 50% of those individuals reported doomscrolling as a coping mechanism even while acknowledging social media as a contributing factor to their anxiety.

It has also been observed that:

In 11 studies, we found that participants typically did not enjoy spending 6 to 15 minutes in a room by themselves with nothing to do but think, that they enjoyed doing mundane external activities much more, and that many preferred to administer electric shocks to themselves instead of being left alone with their thoughts. Most people seem to prefer to be doing something rather than nothing, even if that something is negative.

Anyone who has ever tried meditation can attest to the immediate discomfort of intentionally doing nothing. It’s almost hilarious how quickly the mind rebels against the task.

People undoubtedly even more aware of phenomenon are those that have spent any time in solitary confinement, which about 122,000 Americans experience per year. Solitary confinement was initially concieved through Quaker ideals as the answer to brutal public punishments like flogging and humiliation, as a chance to self-reflect and self-improve, but it didn’t take long for penitentiaries to exploit the practice as a punishment-within-a-punishment, and not much has changed since the 18th century. It turns out that extended isolation is the worst form of punishment that living human beings can experience, and loneliness has been found to have the same impact on health as smoking over a pack of cigarettes a day.

The Department of Health and Human Services recently declared that we are in an epidemic of loneliness and isolation. Social media has been identified as playing a causal role, alongside other factors like our built environment.

“Learned helplessness,” another crucial discovery from the often controversial and depressing psychological research of the 1960s, is at play here. For example, dogs that received a relentless and uncontrollable deluge of electric shocks were found to lie in their cages, even if the door was left open. It was the lack of control that enabled this paralysis. They came to just assume by default that life is pain and there’s nothing you can do about it.

Sound familiar?

So much is out of our control. That same study on Gen Z and anxiety found that bigger contributors to anxiety were financial stress, work, the future, climate change, and other huge problems that feel uncontrollable (and often are, on the individual level). Social media just operates as a conditioned crutch, functionally not much different than other forms of substance use (and considering the impact of loneliness on health, arguably comparably dangerous).

Is the outside world and the scope of our problems so huge, the brokenness of our economic system so demeaning, that we lie in our own open cages like those dogs in the learned helpless studies from the 1960s, unable to leave even though we desperately want to?

In any case, the content we see on social media certainly reinforces that perspective. After all, the majority of news presented online is negative and only 6% is positive.

I don’t think our problems are insurmountable. There’s been too many good things happening, and social media makes it REALLY easy to ignore that and focus on the negative (and remember, human beings prefer negativity — even electric shocks — to boredom).

I also don’t believe social media is going to continue dominating our lives. I agree with Thomas J Bevin, who recently wrote a phenomenal piece on how the “extremely online era” is ending. To paraphrase his main point, it may seem that the era of social media will never die, but so did the Berlin Wall until it suddenly came down.

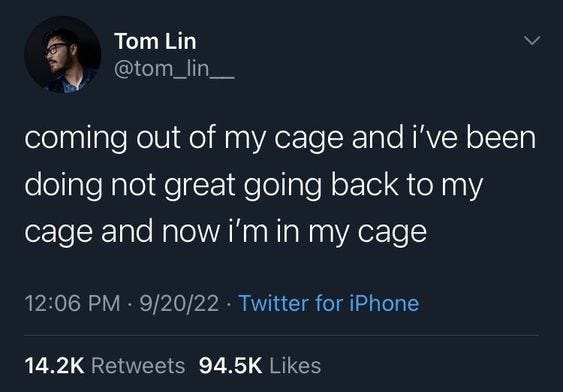

I see things changing, even on social media, where the memes about how awful social media is are becoming one of the most common forms of content.

So don’t worry. You don’t have to go back in the box.