Why "Daihatsu" Millennials Have to 'Fake It 'Til We Make It'

The sheer size of our demographic alone has made things tough for us...but now it might be our biggest advantage.

A while back I introduced y’all to the way I break down Millennials into three micro-generations: the Reagan Millennials (1981-87), Daihatsu Millennials (1988-92), and Zillennials (1993-96). I parceled out these categories based purely on cultural factors, demonstrating how Reagans had a lot in common with latter Gen X while Zillennials have more in common with Gen Z - “in common” defined by culture, technology, approximate age at historical events, and spending habits. Meanwhile, the Daihatsu Millennials — the proverbial middle child — had a fairly unique experience defined mainly by our rather idyllic childhoods:

By the time we got potty trained, the Berlin Wall had just come down, the Soviet Union collapsed, violent crime plummeted by over 40%, jobs were skyrocketing, the federal budget was balanced (we were even paying off the debt), and technology was advancing at jaw-dropping speeds with an optimism for the future that is paralleled only by the Jetson’s. They even called this era the end of history.

That is, of course, until 9/11.

Our ages at the time of that attack (and the following ten years of climate, economic and political disaster) helped shape our micro-generations: Reagan Millennials were 14-20, just entering the job market and old enough to join the military, Zillennials were 5-8, too young to really understand how good things had just been, and Daihatsu Millennials were 9-13, right in the transition to adolescence and just in time to permanently engrave that nihilism into our core programming.

I also compared us to Generation Jones, a micro-generation of those born between 1954 - 1965, or that group of younger Boomers and older Gen X. The name comes from the expression “keeping up with the Joneses,” and this group was originally identified by cultural critic Jonathan Pontell, himself of Gen Jones. For most Millennials, especially Daihatsus, these are our parents. And it turns out we have more in common than culture: there are hard economic realities shaped purely by the sheer size of our demographic.

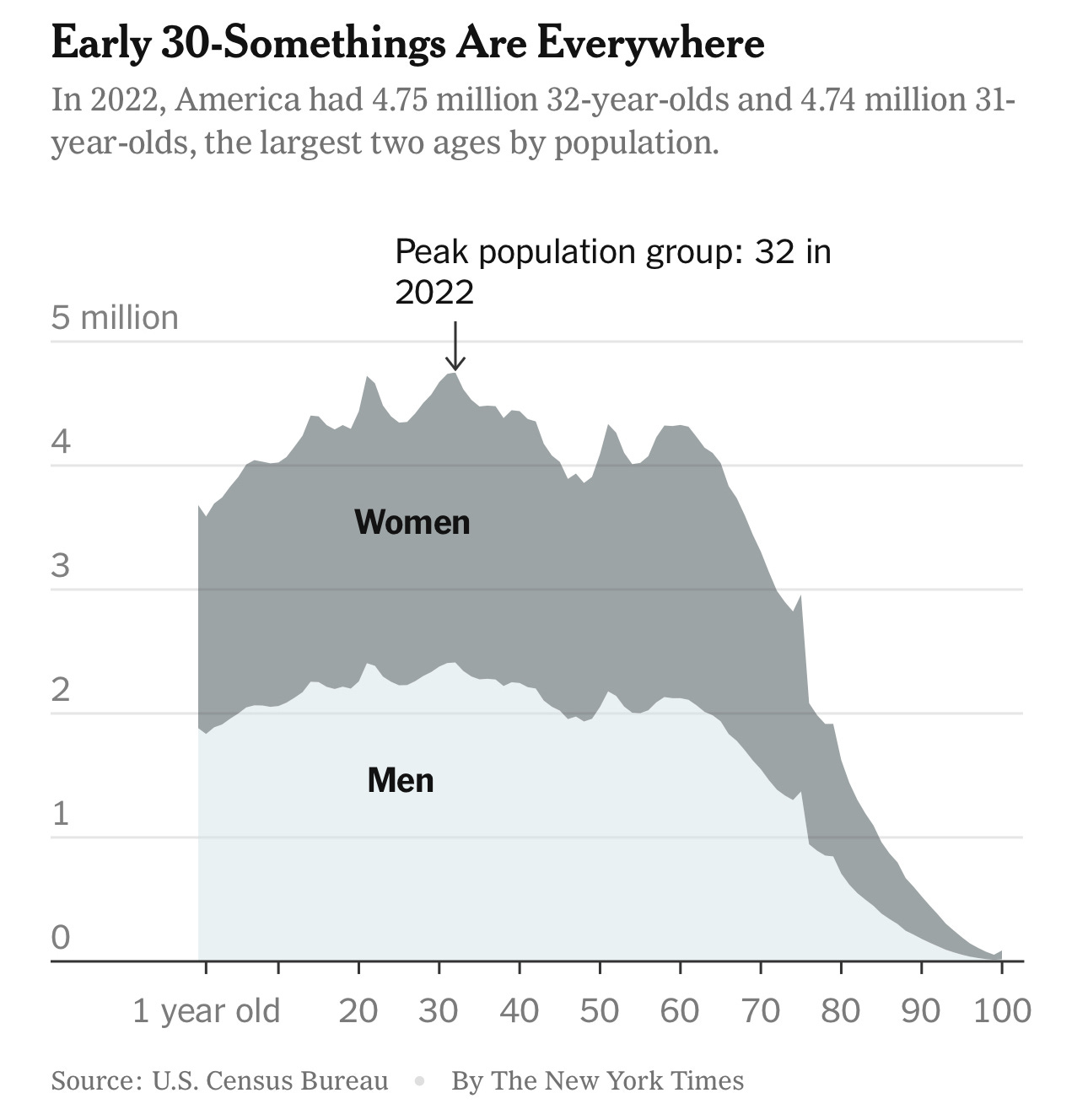

Last week, Jeanna Smialek wrote for the New York Times about how Millennials born in 1990 and 1991 are the peak of America’s population. We make up 13% of all Millennials alone.

It’s pure competition. At every major milestone, there have been more people to compete with: jobs, education, and the big one, housing. There were similar crunches for our parents:

Economic research has suggested that the Baby Boom generation (which included a peak birth cohort born in the early 1960s) faced a tough entry into the labor market as its members competed for a limited supply of jobs. Generation X, or the so-called “Baby Bust,” was smaller — and experienced better outcomes.

Gen Z is a smaller group than Millennials because their parents are mostly Gen X, which was a smaller generation than the Boomers — it’s the inertia of numbers. But for Millennials (especially those of us at the peak of the birth curve), our preferences and spending habits have steered the ship of the economy over the last twenty years. As Smialek points out, when the huge mass of us started applying for colleges, it drove up tuition and even community colleges started turning applicants away. The same thing happened with the cost of rent for apartments in big cities, and now it’s happening to home prices in the suburbs. It’s supply and demand, which has also gone beyond access and defined style. As Smialek writes,

Millennial vacationing and dining-out habits caused research firms to endlessly tout the rise of the “experience economy.” We’ve been accused of killing McMansions and formal dress codes, but we helped to fuel the rise of tiny homes and athleisure.

Smialek makes some tremendous additional points that are worth reading, especially pertaining to questions like: are we liable to face similar risks of homeless as Boomers? Are we going to have as many kids? There are also several key differences that need to be pointed out, but I wanted to focus on some of the takeaways about what it means to have this sizeable power.

As the group increasingly defining the shape and direction of the economy, brand consultants have been researching Millennials for well over a decade, and it turns out we have some pretty consistent values. We want to see that companies engage in meaningful philanthropy and have a net positive impact on the environment and society, we value locally made and often hand-crafted goods, and we care very deeply about being good parents (it’s a cliche, but as a dad myself, the random emotional compliments I get in grocery stores from Boomers for just doing the bare minimum is itself a testament as to a pretty glaring problem that needs to be addressed).

But the biggest thing that defines our tastes? Authenticity.

We’re tired of the bullshit. The moment we were old enough to start to understand how the world works, we saw that all of the adults were making the same mistakes that our textbooks were warning us about. ‘The Vietnam War was a mistake’ meets ‘let’s invade Iraq!’ ‘Here’s the undeniable evidence that our global climate is on the verge of a collapse’ meets ‘drill, baby, drill.’ Right as we learned about how the stock market crash led to the Great Depression, we watched the housing market collapse but the big banks get bailed out. Meanwhile, companies were increasingly selling us cheaper, flimsier crap while flagrantly exploiting workers with low union participation rates not seen since the 1920s.

We have been having to compete in unfair conditions our entire adult lives, and as such have learned how to “fake it ‘til you make it.’ We’re the reason why so many baristas have college degrees; as such we know all the tricks to make our résumés look ever just slightly better than our peers, because we’ve had to. It’s the same thing with college applications, which experimented on us by dropping standardized test scores, requiring more creativity on essays and extracurriculars. We know how to spot a faker because we know better than most what faking it looks like. In fact, while Smialek prefers to call us “peak Millennials,” I still prefer “Daihatsu” because that company has recently been found to have been ‘fakin’ it ‘til they make it’ for forty years.

This is why any hint of authenticity piques our attention. It’s why we care more about experiences than unnecessary high end items like fine china. It’s why we want “cottagecore” homes and won’t stop talking about mental health.

It’s also why we’re an extremely difficult bunch for politicians to win over. That’s just a general statement; politics by its nature requires at least some degree of lying, at least by omission. But this is why Bernie Sanders was most popular among Millennials: he was perceived as the most honest candidate of the bunch.

We — alongside our Gen Z younger siblings, who share a lot of our values and are even angrier and more nihilistic — now make up the largest voting bloc in the country, on top of having the greatest spending power.

Why don’t we consider using it?