The Cicada Elections

1803 and 2024: new election laws, divided politics, and a hell of a lot of bugs

Cicada broods XIII and XIX emerged this year, in sync for the first time since 1803. In a curious twist of fate, the federal elections that followed the dual emergence of these cicada broods — both in 1804 and this coming November — involved multiple changes to the counting and certification of electoral college votes. Congress ratified the 12th Amendment in 1803, setting up the system that has been used in every presidential election since then, and a key phrase from that amendment became a central focus of the legal theory behind Trump’s rejection of the 2020 election results:

The President of the Senate shall, in the presence of the Senate and House of Representatives, open all the certificates and the votes shall then be counted;

We now know Donald Trump pressured Mike Pence to reject the count and “send it back to the states.” However, Mike Pence, asserting (correctly) that he did not have the constitutional authority to do so, refused, and what happened next was totally normal and peaceful.

The election of 1800, which was then sometimes called the “revolution of 1800,” was the first presidential rematch in U.S. history: President John Adams (of the Federalist party) versus Vice President Thomas Jefferson (of the Democratic-Republican party). See, before the 12th Amendment, the electoral college did not differentiate between presidential and vice presidential candidates; whoever got the most votes won, and whoever came in second would be the vice president, even if they came from different parties (as was the case with Adams and Jefferson). Imagine: without the 12th Amendment, Donald Trump would have become Joe Biden’s Vice President in 2020.

The election of 1800 was also the first to use a ticket, wherein the candidate for president announced a running mate, but this required strategically coordinating the electoral college votes so that Jefferson and his running mate Aaron Burr would beat out Adams and his running mate without tying with each other. Obviously this was as convoluted as it sounds, especially when communications depended on letters delivered on horseback. For the 1800 election, at least one Republican elector was supposed to withhold one of his votes for Burr. None of them did, causing a tie between Jefferson and Burr, and this “Burr dilemma” almost caused a constitutional crisis.

Because Jefferson and Burr had tied, this sent the presidential election to the House of Representatives, which was controlled by a substantial majority of the Federalists, the party of John Adams. Many Federalists couldn’t stand Jefferson, not only because of major and depressingly familiar policy disagreements over state’s rights, taxation, the federal bank, and immigration, but because Jefferson had spent the last decade slinging mud (and worse) at John Adams and his predecessor, George Washington. As such, even though Thomas Jefferson carried significant public popularity as a founding father and current vice president, many Federalists threw their support behind Aaron Burr, who refused to confirm that he would turn down the presidency if the House of Representatives voted for him.

Alexander Hamilton, among many others, began denouncing Burr as a self-centered opportunist, and a long, nasty, behind-the-scenes campaign for Jefferson took off, until ultimately Jefferson won re-election two weeks before inauguration day. The Federalist party shortly thereafter collapsed, never winning a presidential race again (hence Jefferson calling it “the revolution of 1800”). Jefferson’s second term would be as consequential as it was controversial, but the year of 1803 in particular — when cicada broods XIII and XIX emerged together — would significantly shape the country we live in today.

Here’s just a handful of some of the significant events: Ohio became the 17th state, Lewis and Clarke were sent out to the Pacific coast from St. Louis, Jean-Jacques Dessalines defeated Napoleon’s army in the Haitian Revolution, and most significantly for our history, the Louisiana Purchase was ratified, nearly doubling the size of U.S. territory.

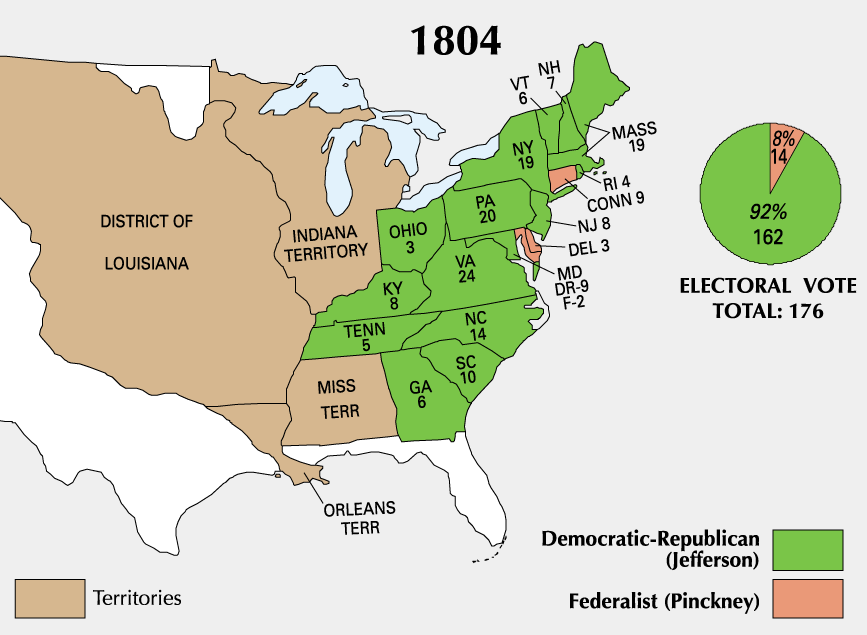

It would take over a hundred years before all the areas covered became states (Louisiana itself was the first in 1812 and New Mexico would be the last in 1912), but this doubling of territory is arguably the most consequential event of the entire Jefferson administration. Consider how different our elections would be without the electoral college votes of the central U.S. Speaking of which, here are the results from the first election to use the rules set by the 12th Amendment:

As it pertained to the cicadas, they, like Lewis and Clarke, found themselves adventuring in lands suddenly called American, irrespective of the Indigenous people who had been living there for millennia, following election law set the same year as the name change.

For Thomas Jefferson, there are additional several striking echoes of our modern times. He was tasked with shrinking the national debt (a whopping $83 million), and he decided to do so by cutting taxes and “useless establishments and expenses,” and closing “unnecessary offices” in the federal government. He felt Alexander Hamilton’s financial system with a central U.S. bank — the predecessor of the Federal Reserve — was a threat to the republic and he tried to dismantle it. He also pardoned multiple people imprisoned under the Alien and Sedition Act, appointed three Supreme Court justices, and launched the “civilization program,” which forced assimilation of Indigenous peoples into U.S. culture. While his rhetoric called for a republic of “independent yeoman farmers” across the continent, his economic policies facilitated the westward expansion of monopolistic slave-run plantations, and this break between ideals and policy would come to define the central conflict of the 19th century, ultimately peaking with the Civil War.

Now we find ourselves facing another consequential election, also one based on new election laws (the Electoral Count Reform and Presidential Transition Improvement Act of 2022 clarifies that the VP’s role is purely ceremonial, changes timing of count submission, specifies rules for challenging the result, and other changes). There’s also a recent history of attempted sedition, multiple wars abroad affecting our domestic politics, spiraling national debt, and antagonism towards the central bank of the U.S. Meanwhile, the most disadvantaged of us, especially in territories that saw a summer full of a hell of a lot of bugs, are feeling left behind and angry.

I wonder what will happen in November. When I first drafted this piece, Joe Biden was the Democratic nominee; now it’s Kamala Harris. If the cicadas held joint assemblies on American politics, they would have last discussed a president who had a Black daughter, born of a slave he owned. This year, they might have discussed the first Black woman to win the nomination for president from a major party. They might find it funny that the parties each share half of the name of Jefferson’s (the Democratic-Republicans), and they probably would not be surprised that we still argue about states’ rights versus the federal government. But at least they’d understand the gist of the term “flyover state.”