"No Definitive Ideology"

Should we be surprised that we don't yet know Thomas Matthew Crooks' motivations?

Though it had been immediately discussed that his political leanings were unclear, the FBI has now officially proclaimed that they found Thomas Matthew Crooks, Donald Trump’s would-be assassin, to have “no definitive ideology … either left-leaning or right-leaning.” After analyzing his internet usage, the FBI found that Crooks had demonstrated “an interest in committing acts of public violence” since at least 2019, with evidence that he had potentially also considered assassinating Joe Biden, Merrick Garland, and members of the British royal family. In response, some said that Crooks’ “profile more closely resembles that of a mass shooter than a politically motivated assassin.”

This may be splitting hairs, but it turns out that in the modern era, most people who assassinate (or attempt to) public officials are rarely motivated by politics. So what even counts as a “politically motivated assassin” anyway, and how is one different than a mass shooter?

A 1997 analysis of American assassins by the Secret Service found that “attackers and near-lethal approachers of public officials rarely had ‘political’ motives.” In other words, if a political leader is shot at, it’s more likely to be a Travis Bickle pulling the trigger than a Gavrilo Princip. More often than not, we’re talking about someone that is socially isolated, has untreated mental illnesses, and a personality that is hungry for fame and social status but a life that does not match their ambitions. The political justifications, if there are any, are usually window dressing.

Consider John Hinckley Jr., whose bullet also came within millimeters of killing a U.S. president. Hinckley had a pretty severe case of erotomania focused on then-child actress Jodie Foster, and, inspired by the film Taxi Driver, he believed killing a president would make her willing to be romantically involved with him. His motivations were certainly apolitical: prior to the attempt to kill Ronald Reagan - whom he even supported for president, according to his parents - he had also stalked Jimmy Carter and had gotten within a foot of him with a loaded pistol.

Or take Sirhan Sirhan, who assassinated Robert F. Kennedy, Sr., due to the latter’s support of Israel. Sirhan was “failing at work, at school, and in social life,” and came to believe that if he shot a national figure (RFK Sr. was just one of several targets he considered), “he could achieve the status he wished for and perhaps even change the situation of the Palestinian people.”

Of course, in looking back through past U.S. presidential assassinations, all four of the “successful” ones seem motivated by politics. But we may not be able to even say that.

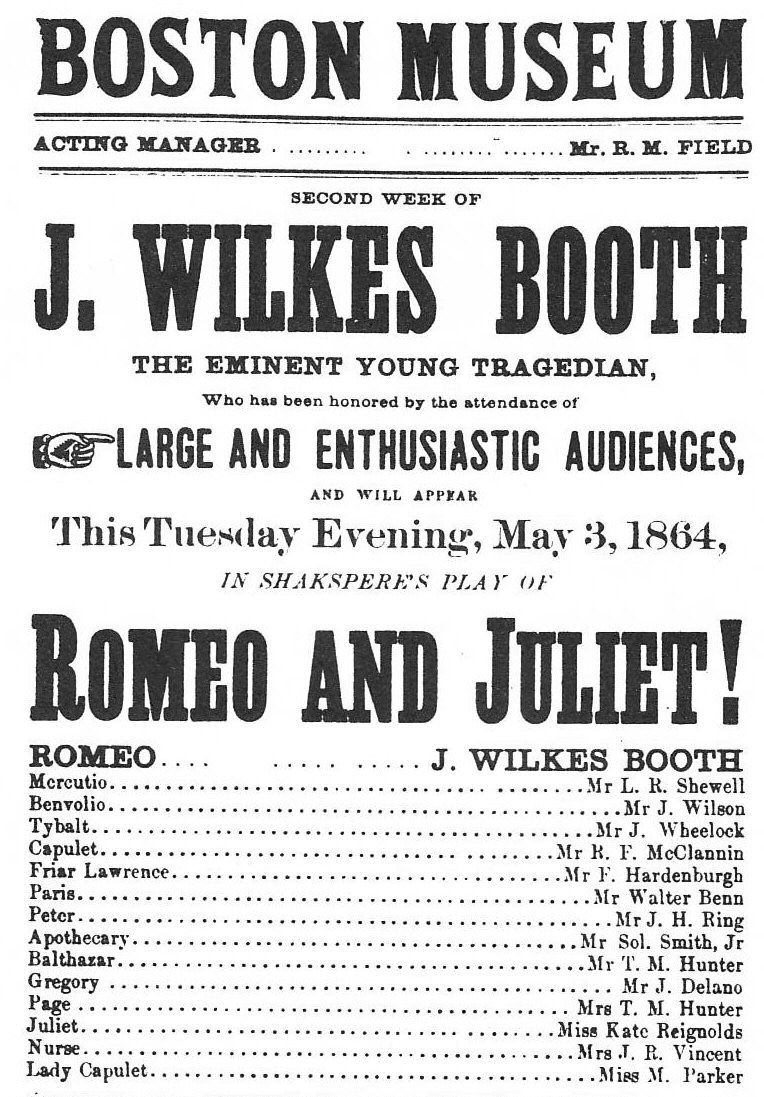

John Wilkes Booth, a Confederate sympathizer, may have been the most purely motivated by politics. Booth was hardly socially isolated; he was a rather successful and famous actor.

There has, however, been speculation that there was an element of shame, ambition, or even sibling rivalry to Booth’s motivation, but frankly, the Civil War had just ended and there had already been widespread political violence for years, and there had already been multiple attempted plots on Lincoln. In this context, the murder seems more like one last act of war.

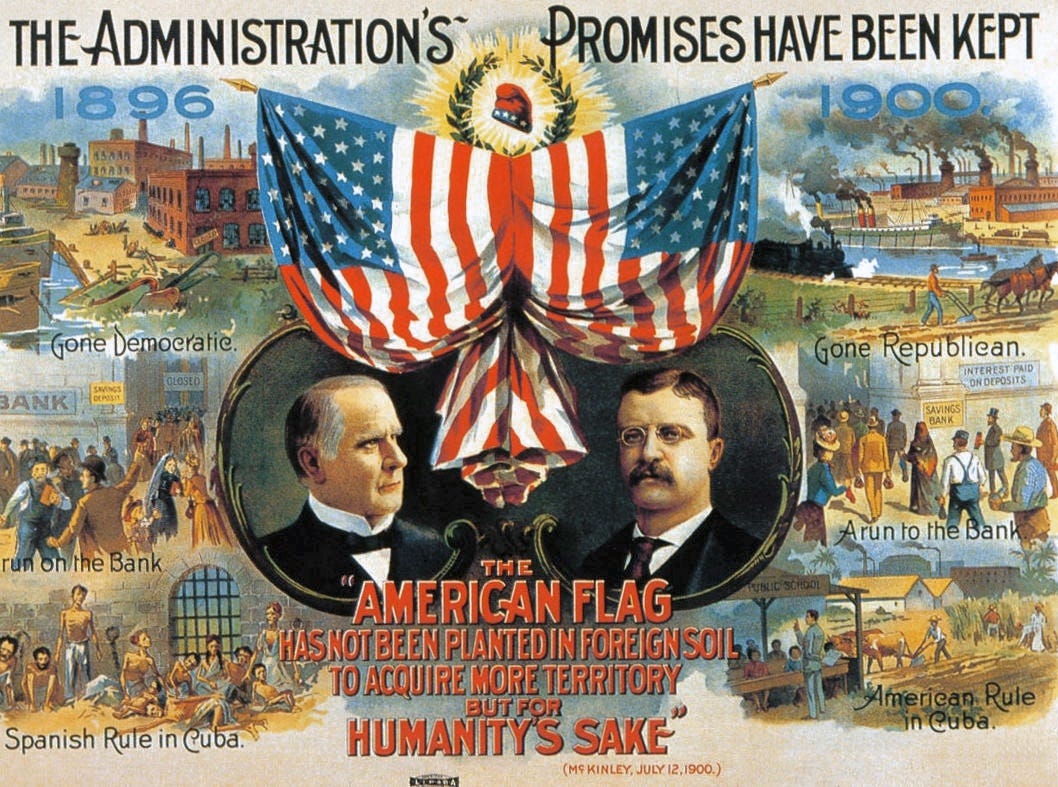

Leon Czolgosz, an anarchist who killed William McKinley, seems also to have been mostly inspired by political motivations, though we start to see some hints of a familiar theme.

Czolgosz, whose mother died when he was only ten, was one of eight children in a poor, working class Polish immigrant family. When he was a young man, the economic crash of 1893 severely impacted him, as did the subsequent mass strikes that followed — especially those that ended in violence. He became increasingly involved in socialist groups, but his increasingly radical beliefs led the socialists to warn each other about him and his desire for violence. Keep in mind that was the Gilded Age, where there was extreme wealth inequality, excessive materialism, widespread political corruption, and U.S. foreign policy was pretty openly imperialistic.

Czolgosz did not find comfort in the Catholic church or immigrant support groups, and he became socially isolated. In the summer of 1900, Czolgosz was inspired by Gaetano Bresci, who publicly proclaimed he assassinated the king of Italy for the “sake of the common man,” and just a year later Czolgosz shot McKinley in the belly point blank twice for the same stated reasoning.

John F. Kennedy…well, for expediency’s sake let’s just agree to say he was either killed because of his anti-communist stances or because of his anti-military-industrial complex stances, so either way you slice it there was a political motivation. Yet the assassin Lee Harvey Oswald’s life was full of tragedy and unanswered help.

An intelligent child but withdrawn and temperamental, prone to acts of violence, even striking his own mother and threatening her and his brother with a pocket knife, Oswald’s father died when he was two months old and his mother was described as “self involved and conflicted,” by the psychiatrist that assessed Oswald in a juvenile reformatory. That same psychiatrist found Oswald to have a “vivid fantasy life, turning around the topics of omnipotence and power, through which he tries to compensate for his present shortcomings and frustrations.”

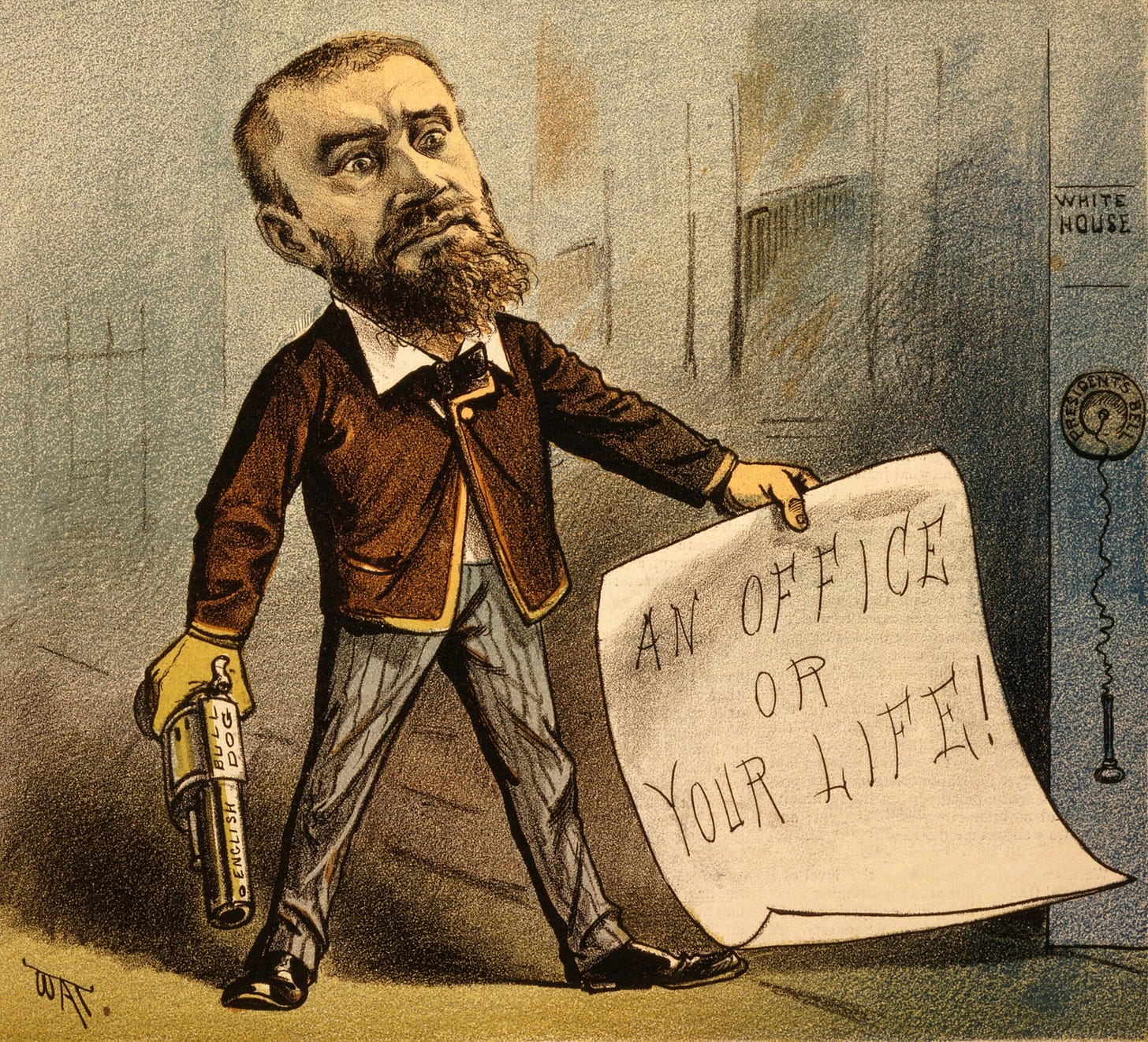

James A. Garfield’s killer, Charles Guiteau, is a bit of an outlier, in that his motivation is dressed in the language of politics but is nakedly delusional.

Believing he played an indispensable role in getting Garfield elected (by self-publishing a rambling speech that he hand-distributed across D.C.), he wandered the city, destitute and disheveled, pestering administration officials relentlessly for a diplomatic appointment to Paris or Vienna. Eventually he came to the conclusion that he would exact revenge on Garfield, so he bought a .442 caliber bulldog pistol with ivory grips that he (correctly) figured would make a great museum piece (it was indeed on display at the Smithsonian until it was lost).

Guiteau’s mother died when he was eight, and he was a “difficult and uncontrollable child with a short attention span and hyperactive habits. He grew into a strange, itinerant, and egotistical adult.” He was intelligent but unfocused; an avid reader and writer but unable to make a meaningful career for himself. A socially isolated failure with childhood wounds.

So when we examine the “successful” assassinations, we see that political motivations are merely painted on top of a predictable pattern.

The same is true of the man who almost assassinated Andrew Jackson. Like with the attempt on Trump, wherein Crooks fired eight times with an assault rifle from a reasonably close distance and missed by millimeters, the failure of the event had stiff odds — Richard Lawrence had two pistols, but both misfired (1 to 125,000 odds). Jackson proceeded to beat the ever loving hell out of him with his walking stick.

Though Lawrence was ultimately found not guilty by reason of insanity, Jackson remained convinced that the entire plot had been orchestrated by the oppositional party, the Whigs. Though there has never been any evidence demonstrating this plot, Martin Van Buren, Jackson’s vice president, was intimidated enough to start carrying two loaded pistols himself everywhere he went thereafter. (Personally, I can’t help but think of this whenever I hear someone say “they tried to kill him,” with regards to Trump. “They?”)

As you probably suspect, descriptions of Lawrence sound so familiar you might be able to even guess them. He was described as a “relatively fine young boy” that was “reserved in his manner; but industrious and of good moral habits.” He moved around a lot and was fairly socially isolated. He had no prior criminal record, but his family noted that he began showing depressive and dissociative symptoms, with occasional violent outbursts. His reasons for trying to kill Jackson had to do with his mental illness; he believed the government owed him money, and Jackson’s efforts to destroy the central bank of the U.S. were prohibiting the payments.

So here’s the point: occasionally, like with Lincoln, you do find assassinations where political justification is the overwhelming motivation. John Wilkes Booth probably would not have assassinated anyone if there had not been the Civil War or the political realities of mid-19th century America. But Lawrence, Guiteau, Oswald, Czolgolsz, Sirhan, Hinckley, and Crooks…the evidence suggests they would have tried to kill someone in the public sector, due to a pattern of social isolation, social failure, unfocused intelligence, and unaddressed childhood trauma.

Here’s the full pattern identified by the Secret Service in 1997, which included analyses of dozens of failed attempts as well:

Almost half had attended some college or graduate education.

Attackers and near-attackers often had histories of mobility and transience.

About two-thirds of all attackers and near-lethal approachers were described as social isolates.

Few had histories of arrests for violent crimes or for crimes that involved weapons.

Few had ever been incarcerated in state or federal prisons before their public figure directed attack or near-lethal approach.

Most attackers and would-be attackers had histories of weapons use, but no formal weapons training.

Many had histories of harassing other persons.

Most are known to have had histories of explosive, angry behavior, but only half of the subjects are known to have had histories of violent behavior.

Many had indicated to someone their willingness to exert violence against government officials.

Attackers and near-lethal approachers often had interests in militant/radical ideas and groups, though few had been members of such groups.

Many had histories of serious depression or despair.

Many are known to have attempted to kill themselves, or known to have considered killing themselves, at some point before their attack or near-lethal approach.

Almost all had histories of grievances and resentments.

Many subjects had contact with mental health professionals or care systems at some point in their lives before their attack or near-lethal approach.

(But relatively few were in contact with mental health professionals or organizations in the year before their attack or near-attack. And few subjects ever indicated to mental health staff that they were considering attacking a public official or public figure.)

Many subjects had histories of delusional ideas.

Few had histories of command hallucinations.

Relatively few had histories of substance abuse, including alcohol.

Thomas Matthew Crooks checks nearly every one of these boxes. Though he had no prior record of violent crime, a clean background check, a passion for history, an associate’s degree in engineering, and two parents who were licensed counselors but no history of prior mental health treatment himself, he also was socially isolated, known by his classmates for being awkward, strange, and for making crass jokes, and he had a search history for “major depressive disorder.” He tried to join his school’s rifle team but failed, and after high school he joined a gun club with a range and began a years long obsession with public assassinations.

It makes sense that we pay so much attention to assassins, would-be or otherwise. The target makes it very easy to notice, remember, and speculate ad insaniam. But when you boil down the facts of their lives — their isolation, loneliness, unaddressed need for mental health help — you don’t get a result much different than that of a mass shooter. Considering that mass shootings and political assassination attempts have both been growing increasingly common, this also points to common underlying causal factors.

Forgive my optimism, but I feel like if we were to fix the systemic failures that enable mass shootings, we could probably make great strides in reducing the incidence of assassination attempts.